Foods To Avoid To Lose Weight- Trigger Foods & Balance

We’ve told 100,000 clients, “There are no bad foods.” And we’re not about to stop. Here’s why.

Candy bars. French fries. Doughnuts. Can most people really include these foods in moderation? Or is that a recipe for a disaster?

By Brian St. Pierre, MS, RD, CSCS

SHARE

At Precision Nutrition, we don’t tell our clients exactly what to eat—or what not to eat.

In fact, we boldly say: “There are no bad foods.”

Our stance tends to spark lots and lots of questions, which is why we decided to take a deep dive into the whole “good foods vs. bad foods” debate.

In this article we’ll:

- explore how good vs. bad thinking can actually set people up to eat MORE of the “bad” foods

- offer an alternative way to think about sweets, chips, and other low-nutrient foods

- provide techniques we use to help to liberate clients from the good vs. bad mindset.

We’ll be honest. The “no bad foods” philosophy can be really scary, especially for people who’ve spent years organizing foods into good and bad categories.

But it can also be equally transformative.

We’ve found that once our clients welcome the foods they love back into their lives—without fear and without guilt—they struggle less, enjoy eating more, and, finally, are able to overcome obstacles that stand between them and their healthy eating goals.

Why the good vs. bad approach just doesn’t work.

Many people divide food into just two categories.

Good foods: Vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, lean meat, and other minimally-processed, nutrient-dense foods.

Bad foods: Sweets, chips, crackers, white bread, fries, and other highly-processed foods that offer little to no nutritional value.

And before we explain why we don’t sort food into “good” and “bad” buckets, we want to be very clear. The nutritional differences between these two categories are quite easy to spot.

Many of the so-called “bad” foods, in high amounts, can raise the risk for a variety of diseases.

They’re also incredibly hard to resist. (The food industry really has created cheap, easily accessible products that our taste buds and brains love.)

But are they bad?

We don’t use that terminology—for six major reasons.

Reason #1: One single food doesn’t define your entire diet.

Maybe you’ve heard of a teenager who ate just four foods for most of his life: fries, chips, white bread, and processed pork.1

And then he went blind.

It’s a cautionary tale, for sure, but it’s important to keep one thing in perspective: That teen is an outlier. Most people don’t eat just four foods.

They eat a variety.

And the fries, chips, bread, and pork didn’t cause the teen’s blindness directly.

They caused it indirectly—by crowding out foods needed for good eye health.

What truly matters for good health? Balance.

In other words, you don’t want your toaster pastries, spray cheese-like product, and crescent rolls to crowd out veggies, fruit, beans, nuts, fresh meats, seafood, and other nutrient-dense whole foods.

If they do, like the teen we mentioned, you run the risk of deficiency.

So the question is: Are you in balance?

We experience massive benefits (fat loss, improved health) when we go from poor nutrition to average or above average.

But eventually, we see diminishing returns.

As this chart shows, not only are gains much harder to see after 80 to 90 percent of your diet is composed of whole, minimally-processed foods, you also run the risk of eating disorders like orthorexia (an unhealthy obsession with healthy eating).

Is most (80 to 90 percent) of what you eat nutrient-dense and minimally processed? (Think veggies, fruit, meat, fish, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, whole grains.) Then there’s likely room for less nutritious foods.

Is most of what you eat highly-processed and nutrient-poor? (Think sweets and chips.) Consider small actions to make your diet just a little bit better. Slowly add more nutrient-dense foods (veggies, fruit, fish, poultry, and so on) to each meal. Use our “What Should I Eat?” infographic for guidance.

Reason #2: No one food is bad for all people in all situations.

To illustrate this point, Precision Nutrition Master Coach Kate Solovieva often brings up cola.

Many people see it as a bad food. Because it’s loaded with sugar and lacking in vitamins and minerals.

But is cola bad in all situations?

“Let’s say you’re visiting a country with no safe drinking water,” says Solovieva. “In that case, cola—with its air-tight seal—is a much better option than water.”

Or, maybe you’re sixty sweaty miles into a 100-mile bike race and your blood sugar is so low that you’re hallucinating flying pink elephants. In that case, the sugar and caffeine in the cola might make the difference between finishing the race and a DNF.

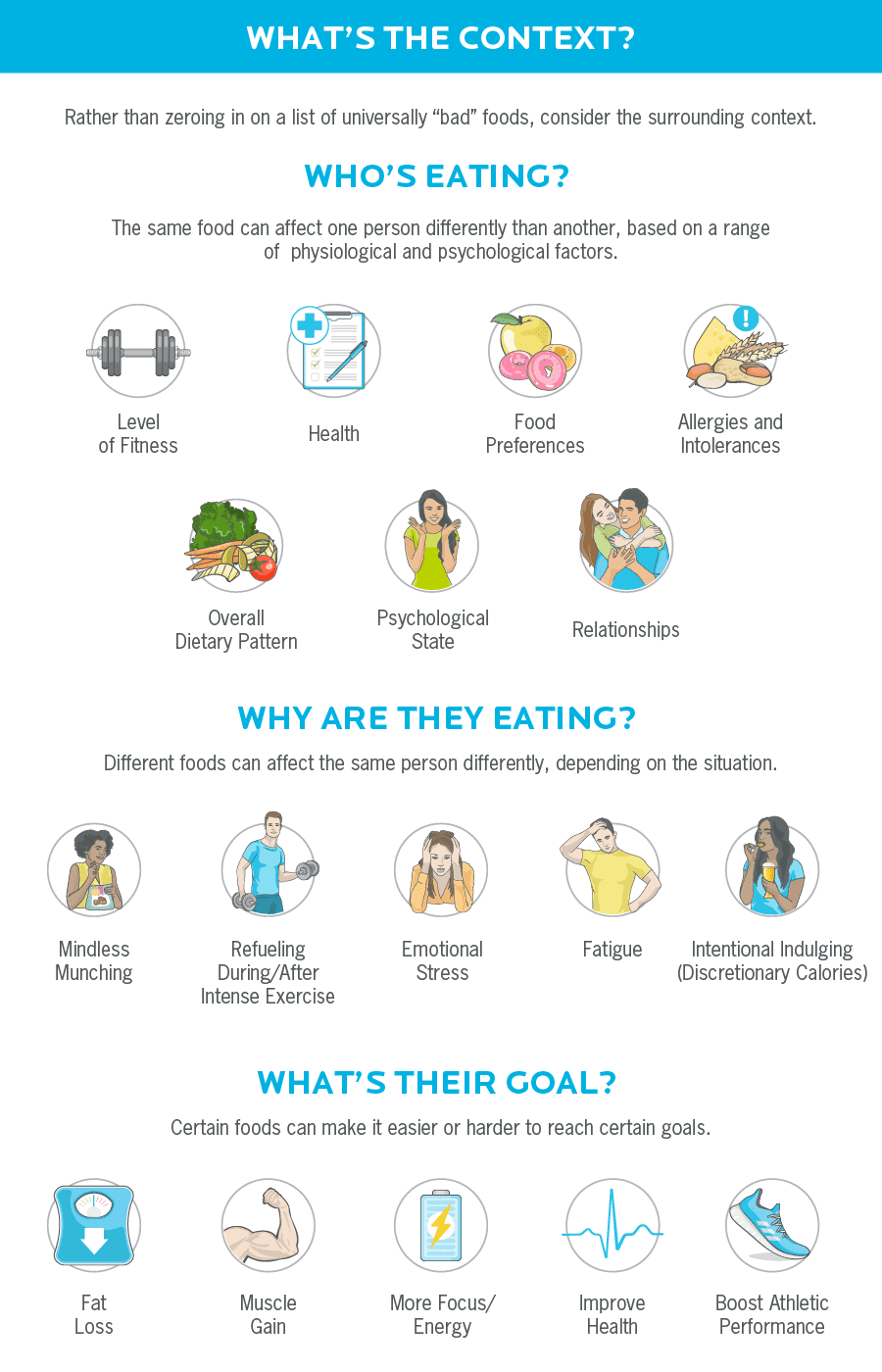

Our individual physiology and psychology also affect what happens when we eat specific foods.

Added sugar, for example, affects someone with type 2 diabetes differently than it affects someone whose cells are insulin sensitive. And it can affect the same person differently depending on whether they’re sleep deprived.

At PN, we talk a lot about deep health—which describes so much more than our weight, cholesterol level, and blood sugar.

Deep health includes where we live and how we feel and who we spend time with. It’s about every aspect of who we are.

When you consider health in this light, the exact foods become less important, and the overall eating pattern and full context of someone’s life becomes a lot more important.

Reason #3: Demonizing certain foods can make them even more appealing.

Lots of people tell us that 100 percent abstaining from “bad foods” is the only way they can maintain any smidgen of control around their eating.

If they say “okay” to one “bad” food, they worry they’ll open the floodgates to a diet swollen with cookies, brownies, chips, and fries—as well as devoid of veggies and other whole foods.

Here’s the thing:

There’s a subtle difference between demonizing a food and merely abstaining from it because you know you tend to overeat it.

When we demonize foods, we “moralize these foods—thinking of ourselves as bad people for eating them,” says Solovieva.

This paradoxically can increase our desire for the very foods we’re trying not to eat. When researchers from Arizona State University showed dieters negative messages about unhealthy foods, the dieters experienced increased cravings for those foods—and ate more of them.2

It’s true that some people can restrict certain “bad” foods for a while.

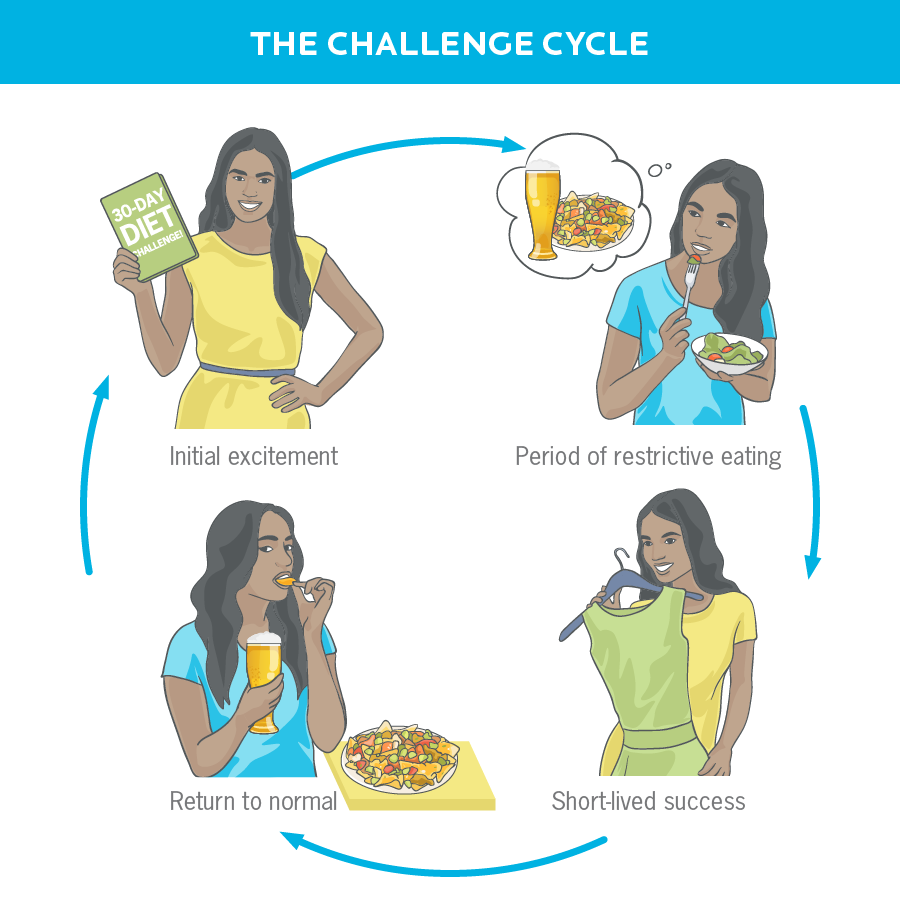

But, for a lot of people, cravings eventually overwhelm their ability to restrict. And when they eat something “bad”—they feel guilty. So they eat even more—and may even stop trying to reach their goals. This can create a vicious circle, as the graphic below shows.

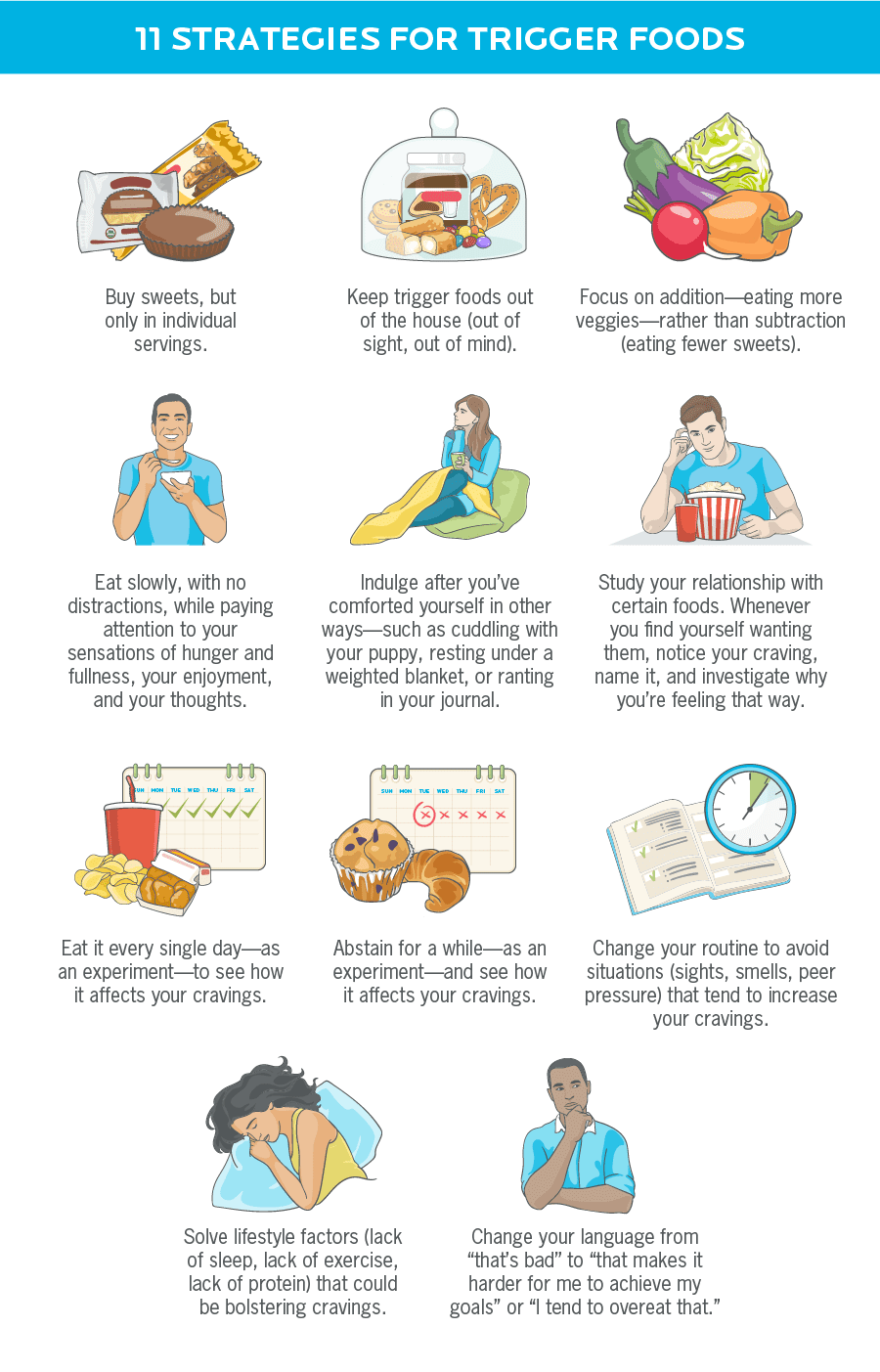

Now, let us be clear: For some people, certain foods may not be worth the struggle—at least for now. They may decide that, if they’re around certain foods, they’re going to overeat them. So they get them out of the house.

And that strategy can work. In fact, we encourage our clients to do kitchen makeovers and remove foods they tend to overeat.

But it’s not the same thing as labeling a food as “bad.”

When we label foods “something I tend to overeat” rather than “bad,” we’re better able to relax, remain flexible, and, potentially, grow into someone who can enjoy the same food, in moderation.

Reason #4: Categorizing foods as “good” and “bad” can work—but usually only for a while.

Having coached more than 100,000 clients, we can say with confidence that “all or nothing” rarely gets us “all.”

Instead, it often gets us nothing.

For example, when someone decides to stop eating “bad” foods, usually they try really hard to stay true to their goal. They’re committed, and they even may stick to avoiding a long list of forbidden foods… for a bit.

But then something goes wrong.

Maybe they go to work and find that a coworker left homemade brownies on their desk.

Or every part of their day goes sideways and, in the evening, they find themselves head down in a gallon of chocolate chip cookie dough as they think “This is bad.”

Or they’re driving for hours to visit relatives, pull into a rest stop, and all they find to eat: the stuff on their forbidden foods list.

Rigidity—good or bad, all or nothing—is the enemy of consistency.

But on the flipside, flexibility helps you stay more consistent. That’s because it allows you to lean into all the solutions available to you.

Flexibility also frees people to use internal guidance—rather than someone else’s external rules—to decide what foods to eat, when to eat them, and why.

So, for example, rather than avoiding sugar just because a health site told them to stop eating it, someone might consider:

- Am I hungry?

- Am I stressed?

- Is this food worth it to me?

- What else have I eaten today?

- What would allow me to truly enjoy this food—without going overboard?

That internal guidance might allow that person with the brownie to say, “You know, I really like brownies, but I’m going to save this until after lunch, when I’m not as hungry, so I can eat it slowly and truly savor it.”

Or that person who is head down in the gallon of ice cream to say, “Okay, so this was probably more ice cream than my body really needed. True. No getting around that. How can I avoid feeling this triggered in the future? And are there other ways I can comfort myself that don’t involve raiding the freezer?”

And for that person at the rest stop, flexibility allows them to scan their choices and opt for the best meal for them at that moment.

Reason #5: It’s really okay—and completely normal—to eat for pleasure.

Food serves many purposes far beyond just flooding someone’s body with nutrients and calories.

Some foods aren’t necessarily loaded with nutrients, but they:

- Taste amazing.

- Connect us with friends and families.

- Create a sense of belonging.

- Make celebrations worthwhile.

In other words, food isn’t just fuel. It’s also love and culture and pleasure—and a whole lot more.

When you think about food in this way, everything—even your grandma’s special black forest cake—can have a purpose and a place.

Rather than a list of foods you can or can’t eat, you instead have choices. You have foods you choose to eat for energy, for pleasure, for health, and many other important reasons.

Reason #6: When we obsess over “bad foods,” we rob ourselves of the ability to evolve.

Rigidly abstaining can teach us to get really good at… abstaining.

And if you’re okay with abstaining from a long list of foods for the rest of your life, there’s nothing wrong with that approach.

But if you’re not okay with a life sentence of no cookies, no brownies, no cake, no bread, and no pasta, then you may be happy to learn that there’s an alternative approach. It involves getting curious about why you struggle to moderate your consumption of certain foods.

Consider:

What leads to feeling out-of-control?

What triggers the “I need this” and the “I can’t stop eating this” thoughts?

When is it possible to eat this food in moderate amounts (if ever)? When isn’t it?

The point: Rather than zeroing in on “bad foods,” look for the underlying reasons (called triggers) that lead you to struggle.

A trigger can be a:

- Feeling. We might eat more when we’re stressed, lonely, or bored. Food fills the void.

- Time of day. We always have a cookie at 11 am, or a soda at 3 pm. It’s just part of our routine.

- Social setting. Hey, everyone else is having beer and chicken wings, so might as well join the happy hour!

- Place. For some reason, a dark movie theater or our parents’ kitchen might make us want to munch.

- Thought pattern. Thinking “I deserve this” or “Life is too hard to chew kale” might steer us toward the drive-thru window.

To uncover triggers, we often ask our clients to keep a food journal—writing down everything they eat and drink for a week or two. When they find themselves craving or feeling out of control, we ask them to jot down the answers to questions like:

- What am I feeling?

- What time is it?

- Who am I with?

- Where am I?

- What thoughts am I having?

They approach it with a “feedback not failure” mentality.

The point isn’t to catch them doing something wrong. It’s to help them assess what’s really going on.

Once we understand why our clients are reaching for these foods, we’re better-equipped to suggest actions that truly help them move towards a healthier relationship with all foods.

One Man’s Evolution Away From Bad Foods

Dominic Matteo grew up reading bodybuilding magazines. For most of his life, he thought of veggies, chicken breast, egg whites, sweet potatoes, oats, and a few other foods as “good.”

All other foods? Bad.

These distinctions didn’t bother him when he wasn’t trying to shed fat.

But once he started trying to restrict his intake, the label “bad” functioned like a tractor beam that drew him straight to the ice cream.

“That’s when I was like, ‘Oh, this is a problem,’” he says.

For several months, he completely abstained from all sweets. He just didn’t eat sugar—at all.

But he knew that wasn’t a sustainable—or enjoyable—way to live.

After applying Precision Nutrition strategies, however, Matteo started to view his list of bad foods differently. Rather than seeing ice cream as “bad,” he thought of it as “a food I enjoy, but slows my progress.”

That new label allowed him to consider how and under what conditions he would coexist with this sweet treat.

“Now, if I do eat it, it will be under certain conditions that I can feel happy about,” he says.

For example, he loves to indulge in ice cream from shops that make it fresh that day. But lower-quality ice cream isn’t worth it for him.

Today, Matteo is more than 100 pounds lighter and, as a Precision Nutrition Master Coach, he’s helping others to follow in his footsteps.

“If there are no good or bad foods, how can anyone ever know what to eat—and what to limit?”

We hear this a lot.

That’s because some people assume that “no bad foods” is synonymous with “all foods are good so eat whatever you want.”

But that’s not what we’re saying at all.

We are, however, saying this: Rather than sorting food into just two buckets—good and bad—it’s usually more helpful for most people to see food as a continuum of eat more, eat some, and eat less.

This might, at first, merely sound like another way to sort food into categories.

But it’s not.

Unlike lists of bad foods, which tend to be universally rigid, a continuum “allows everything to be contextual and personalized,” explains Precision Nutrition Master Coach Dominic Matteo.

“If my goal is muscle gain, my continuum will look different than if my goal is fat loss,” Matteo says.

Once people define that continuum for themselves, we then work with them to find ways to include more “eat more” foods and fewer “eat less” foods, aiming to make each meal just a little bit better.

For example, before Matteo became a Precision Nutrition Master Coach, he was a client who wanted to lose fat. This is how “just a little bit better” looked like for him for a specific fast food lunch.

He eventually ended up in a similar place that some forbidden foods lists may have sent him, but he did it in small steps, and in a way that was ultimately more sustainable.

What’s more, it didn’t mean he could never have a double bacon cheeseburger again. Sometimes he does, but he enjoys it—on his terms.

“My client believes in bad foods—as if they were a religion. Help!”

Saying, “there are no bad foods” usually results in a blank stare.

So, pretend you don’t know the answers, says Kate Solovieva.

Assume a poker face, and ask questions that seem obvious.

What follows is a conversation Solovieva had with a client about this very topic.

Client: Bad foods are my problem. I need to cut them out. I just can’t eat them.

Coach: So, can you tell me a little bit more. When you talk about cutting out the bad foods, what does that look like?

Client: Taking sugar out of my diet.

Coach: So when you say sugar, what are some of the things you are thinking of?

Client: Cookies. Pastries. Chocolate—chocolate is my weakness.

Coach: So… you really enjoy chocolate?

Client: I do.

Coach: Help me understand. What is it that you enjoy?

Client: I don’t know if it’s the rush of eating the chocolate bar itself. Or maybe it’s the fact that I don’t have it all the time. I don’t know. There’s something about chocolate.

Coach: So, in some ways, it makes you feel super good. And it obviously gives you pleasure. What makes you label it as bad?

Client: It’s the high-calorie count and the amount—the portion.

Coach: So the high number of calories makes it bad? Can you explain?

Client: Well, for me, it leads to weight gain.

Coach: So what I am hearing is that it’s not the chocolate that’s bad. It’s the weight gain that’s bad. Is that right?

Client: Pretty much. Exactly.

Coach: So I’m curious about something you said. You love chocolate. You enjoy it. You like the taste of it. When I asked why it’s bad, you told me about the calories and the portions. Can you tell me more?

Client: Well, I can’t just have one or two squares. Ideally I should have no more than five squares—half a bar. But I don’t have that control. The moment I taste it, I have to have more and more and more.

Coach: So what happens when you don’t have chocolate at all?

Client: I’ve gone months without it. And it’s great! But then I end up eating it—like on a special occasion. And then I binge. And then everything goes downhill. So I’m better off not having it at all.

Coach: What do you think would happen if you had a little bit… everyday? Like on purpose.

Client: I don’t know…I don’t think I have that control. Should I try that?

Coach: I don’t know. Should you?

Client: (Sounding tentative) Sure, maybe I can try that?

Coach: Well, what I am hearing is that you enjoy it. And it sounds like the bingeing behavior is happening because you don’t have it every day. So maybe you can try this as an experiment. Maybe you see what happens if, every single day, you have this thing that you enjoy. And when you eat it, if you want more, you can just remind yourself that you can have more—tomorrow. Are you with me?

Client: Yes.

Coach: It’s a scary experiment. But if you decide to give it a shot, let me know, okay?

Client: Okay, I will. I’m kinda nervous about it, but I will try it.

And then the conversation can go on to define the experiment: How much chocolate? What time of day? How will you eat it?

And no matter what the client ultimately does—whether the client tries the suggestion or not—“you’re in a position for them to come back to you without feeling judged,” Solovieva says.

“Isn’t it just easier to not eat certain foods?”

For some people in some situations at certain points in their journey: yes.

But this need to abstain doesn’t have to be a permanent situation. Once they develop a range of habits, many people can shift from abstaining from certain foods to moderating them.

That’s why we like to ask our clients to consider two questions about the foods they think of as bad:

What does this food do—for you?

What would you like it to do?

For example, maybe, right now, certain foods make you feel out of control because you struggle to stop eating them once you start. But you’d like them to merely become foods you enjoy in moderation.

What are all of the possible ways of going from point A (out of control) to point B (something I enjoy in moderation)?

There are dozens of other possibilities that we didn’t even list on the chart above. You might try one. You might try several. You might try all of them.

The point: You may find that liberating yourself from the good vs. bad mindset frees you to see more possibilities than ever before.

And, along the way, you may also discover that this broader, more flexible mindset allows you not only to enjoy every meal a heck of a lot more—but also to reach your goals more quickly.